PhD Founders: Your Degree is Probably Working Against You

How to flip the meme and build a real company in healthcare

I say this as a PhD who made basically every mistake you can make building a company and fundraising.

When a VC sees "PhD" on your bio, an unspoken meme pops up: This person will burn a lot of money doing beautiful research and never build a business.

They won't say it that bluntly. But they're afraid you'd rather run experiments than sit with customers who might say "no." That you'll over-engineer everything and take twelve months to do what a scrappy team would ship in six weeks.

They want you to prove someone will pay before you build the cathedral.

William Draper III — one of Silicon Valley's founding venture capitalists — listed two great regrets when reflecting on his career in his book, The Startup Game. The first was not investing in Apple when he had the chance.

The second was backing PhDs.

Why? PhD founders treated venture capital like grant funding. They optimized for elegance instead of shipped and sold. They confused technical risk — can we build it? — with market risk — will anyone pay? They burned capital slowly and beautifully while the market moved on.

If you're a PhD founder, your job is to create the anti-meme. You must go further than a non-PhD to prove you're not that caricature.

I did exactly this

CliniCast, my first startup, taught me everything by doing it backwards.

Physics PhD, moved into healthcare data science with a clear theory: algorithms would matter most, then data, then healthcare systems.

Reality was inverted.

Healthcare systems mattered most, followed by data, and then algorithms.

In 2011, I founded CliniCast to solve what I thought was a huge problem: using EHR data for predictive analytics. This was wrong in three compounding ways.

First, the problem didn't exist the way I thought.

EHR data was too inconsistent to provide a single source of truth. I assumed I could know a health system's data better than they did, which is laughable. Please laugh at anyone who tells you this.

Second, the economics were broken.

By the time you get access to the data and apply open source tools that a graduate student could use, you've lost all pricing power. The joke about the PhD selling ice cream and getting paid for the ice cream rang hollow for me in 2012.

Third, I got lucky and found the pivot.

Clinical trials make health systems money. Finding patients for clinical trials is a manual headache. We built an optimized search tool for trial matching and scaled it quickly because the value was obvious and immediate.

Then we made it repeatable, and I sold when someone put a check in front of me.

What investors actually want to see

Lead with customers, not credentials. Ship embarrassing v0s. Make business milestones your scoreboard.

If you're a PhD founder, assume you start in a hole. Here's the rope:

Customer proof:

10+ discovery interviews by segment

3–5 pilots with time-to-first-value in under 90 days

Paying customers or letters of intent

Unit economics:

Gross margin above 60%

Payback period of under 12 months

LTV/CAC above 3x

Evidence: Not "we built a model" but "this changed behavior by X% with baseline and counterfactual."

Operational readiness for healthcare:

SOC 2/HIPAA posture

EHR integration depth (Epic/HL7/FHIR)

Clinical workflow fit: who clicks what when

Bring in non-PhD DNA early. Product, sales, GTM, ops. People who love humans as much as you love hard problems.

Use the PhD where it's an actual advantage — deep tech, credibility with technical buyers, complex domain pattern-matching. But treat it as a tool, not your identity.

A Wharton study by Hong, Guo, Zhang, and Hsu analyzed thousands of ventures and found research-oriented founders outperform matched peers when they build in their domain of expertise — about four percentage points better exit rate and nearly two percentage points better on "good exits." But they significantly underperform when they venture outside their domain.3

Stay close to your advantage and add complementary talent early.

The margins are the whole game

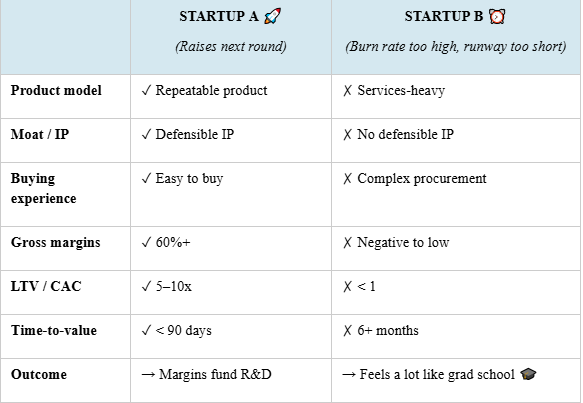

Two startups. One raises the next round. One doesn't.

Startup A:

Repeatable product with defensible IP. Easy to buy. Throws off fat margins that fund R&D. LTV/CAC is enormous — 5x, 10x, higher.

This is a very, very good company.

If your PhD drives those pieces — the IP, the R&D effort, and yes, saying the quiet part out loud, the monopoly pricing — you're gold.

Startup B:

Lots of services to implement. Not repeatable. Slow customers. Hard to buy. Indefensible IP. LTV/CAC is less than A’s.

This is a very bad company on a timer - burn rate too high, runway too short to hit the milestones you need for the next round.

You're unlikely to raise the next round without some serious, wrenching change.

You want to be Startup A.

If Startup B sounds like your graduate program — bespoke work for each committee member, slow approvals, hard to navigate, no repeatable process, unclear value to the outside world — you probably understand why PhDs aren't lauded but derided.

The uncomfortable truth

Your customers define your success.2

Repeatable, good economic businesses create the positive feedback cycles that make your PhD experience valuable.

Internalize that and you'll do the opposite of your default instincts more often.

The PhD gives you technical depth, domain credibility, and the ability to navigate complexity.

Real advantages.

But only if you pair them with customer obsession, operational discipline, and willingness to ship before you're ready.

The scoreboard is revenue.

Footnotes

William Draper, The Startup Game. 2011.

Your customers are your best reference. If you ever forget this, see reference [2].

Research-oriented founders: Hong, Suting, Kaihao Guo, Haipeng Zhang, and David H. Hsu. "When Do Ventures Founded by Research-Oriented Entrepreneurs Outperform?" August 2022. The study examined matched samples of several thousand ventures and found research-oriented founders outperform in their domain of expertise (~+4 percentage point exit rate; ~+1.8 percentage point "good exit" rate) but underperform outside their domain. Full paper. ↩

Glossary

Discovery interviews: Conversations where you shut up and let potential customers tell you their actual problems, not the ones you assumed they have.

Pilots: Time-boxed tests with real users doing real work — not demos where you drive the mouse.

Time-to-first-value: How fast someone sees a concrete win from your product; if it's longer than a quarter, you're selling enterprise software the hard way.

Letters of intent: Written commitments that fall somewhere between "we're interested" and a signed contract; better than nothing, worse than revenue.

Gross margin: Revenue minus direct costs of delivering the product, expressed as a percentage; software should be 60%+, services-heavy models struggle to break 40%.

Payback: How many months it takes to recover the cost of acquiring a customer; under 12 months means you can grow without running out of cash.

LTV/CAC: Lifetime value of a customer divided by cost to acquire them; 3x is acceptable, 5-10x is excellent, under 1x means you're paying people to use your product.

Baseline and counterfactual: What happened before your intervention versus what would have happened without it; the difference is your actual impact, not your aspirational impact.

SOC 2: Security audit framework that proves you handle data responsibly; table stakes for selling to enterprises.

HIPAA: Healthcare privacy law that makes everything harder and more expensive; non-negotiable if you touch patient data.

Epic/HL7/FHIR: The trinity of healthcare data standards — Epic is the dominant EHR vendor, HL7 is the legacy messaging standard, FHIR is the modern API standard that's slowly replacing it.

Clinical workflow fit: Whether your product slots into the five seconds a clinician has between patients, or requires them to completely rebuild their day.