Healthcare System Stakeholders Cheat Sheet

A not-so-brief guide to our healthcare stakeholders: providers, payers, pharma, and patients

The U.S. “healthcare system” is so vast it’s fair to ask whether it’s really a system at all, or more like a patchwork of many systems stitched together. In fact, it’s slow large, if U.S. healthcare were its own economy, it would rank as the fourth-largest country in the world by GDP.

Patients, providers, payers, pharma, regulators, researchers—all interconnected, all with competing incentives. The result is a system that delivers some of the best care in the world, but is plagued by cost, access, and quality challenges.

This article will cover the four P’s of healthcare—Providers, Payers, Pharma, and Patients—and how each one shapes (and complicates) the system we all have to navigate.

Providers: the people and institutions delivering care

At the heart of the U.S. healthcare system are our healthcare providers. These are the doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers who deliver direct care to patients. They operate in a variety of settings, ranging from private practices and hospital systems to nursing homes and home healthcare.

Hospitals

Healthcare providers in the U.S. are largely private. According to data from the American Hospital Association, approximately 49% of hospitals are non-profit, 20% are for-profit, and 18% are government-owned. There are nearly 1M beds across these hospitals, and there were over 34M admissions in 2021.

Just because a hospital is a non-profit does not mean it does not profit. In fact, one study found that mean operating profits in 2019 were $58.6M for nonprofit hospitals and $43.4M for for-profit hospitals. But they use those profits to provide charity care, right? Actually, nonprofit hospitals have been found to have worse ratios of charity care to total expenses than for-profit hospitals. And 86% of nonprofit hospitals do not provide more charity care than the value of their tax exemption. So while 49% of hospitals are nonprofit, they may not necessarily be fulfilling the charitable mission that their tax-exempt status implies. This raises important questions about the accountability and social responsibility of nonprofit hospitals, leading to a broader debate on how healthcare should be delivered and financed in a way that prioritizes patient care and public health.

Another important thing to understand is how hospitals set prices and get paid. Hospitals create a “chargemaster” list of all billable activities, which they are now required to publish (you can find them online; here are all hospitals in California). Private insurers generally negotiate a discount to the chargemaster. And public insurers (Medicare) pay the lowest rates given they set their own prices using something called Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS). The ones who pay the most are uninsured, cash-paying patients.

Physicians

The number of physicians in the United States has been on an upward trajectory. Today, there are over 1 million active physicians, an increase of more than 17% over the last decade. This number is growing mostly because of an increase in specialists. The number (and percent) of primary care physicians (PCPs) has actually fallen in this time.

Yet many believe we are facing a looming physician shortage, with estimates from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) suggesting a shortfall of between 37,800 and 124,000 physicians by 2034. What’s driving the shortage? The time and cost of medical training, increasing physician burnout, rising malpractice suits, and growing disenchantment with the complexities and inefficiencies of the healthcare system.

Nurses

As the most trusted profession for the last 20 years, nurses make up the highest percentage of the US healthcare workforce and serve as the primary providers of patient care.

We know the critical role nurses play in our healthcare system. They are the backbone of patient care. A 2018 meta-analysis found that the higher the level of nurse staffing in a hospital, the fewer patient deaths there were.

A 2018 meta-analysis found that the higher the level of nurse staffing in a hospital, the fewer patient deaths there were.

Unfortunately, we’re also facing a nursing crisis and looming shortage. One study showed that more than 70% of healthcare workers in the country have symptoms of anxiety and depression, 38% have symptoms of PTSD, and 15% have had recent thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

The pandemic exacerbated the looming nursing shortage across the country. And a recent McKinsey survey found that more than 30% of nurses are currently thinking of leaving direct patient care. Not only will this be an even bigger strain on the nurses who stay, but it also puts patients' lives at risk.

Pharmacists

Pharmacists play a crucial, often under-appreciated, role in our healthcare system. These highly-trained professionals are not simply dispensers of medication; they are an integral part of the healthcare team, providing patient care that optimizes the use of medication and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention.

The scope of pharmacists' roles has expanded significantly over the years. They now provide even more services, including administering vaccinations, conducting health and wellness screenings, providing personalized medication counseling, and managing chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma, and hypertension in collaboration with other healthcare providers.

Pharmacists are one of the most accessible healthcare professionals. The vast majority of Americans live within five miles of a pharmacy, providing easy access to patients, particularly those in otherwise underserved areas. This accessibility puts pharmacists in a prime position to act as front-line healthcare providers, answering patients' questions and addressing health concerns.

Payers: the money side of access

Access to healthcare in the US largely hinges on health insurance. This system, rather than a single-payer or entirely government-funded model, is the dominant method of accessing and paying for healthcare services.

Employment-based insurance

Most Americans access health insurance through their employers, which is bonkers since people stay in jobs on average for four years. I can’t even count how many health plans I’ve been on, and the headache every time I need to select a new plan.

Employment-based health insurance is a quirk in our system that was solidified during World War II, when, due to wage and price controls, employers began providing health benefits to attract and retain employees (a practice further encouraged by the IRS's tax-deductible status for these contributions).

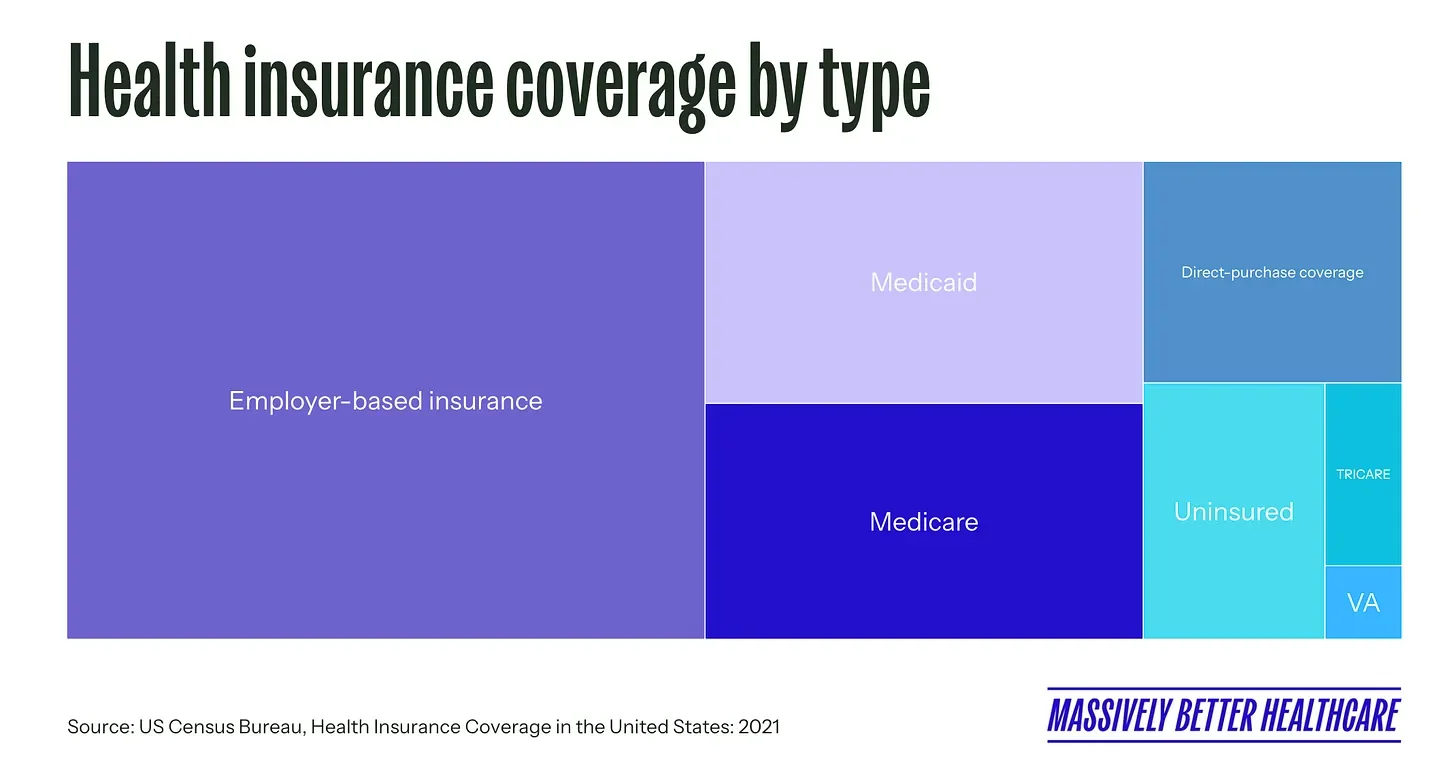

Today, employer-sponsored plans cover about half of the population. These plans are primarily provided by private insurance companies, although employers bear a significant portion of the costs.

This model of health coverage has disadvantages:

Job-lock. This is when people feel stuck in their job because they need the benefits, reducing mobility across jobs, and creating inefficiency in the labor market. And it means employees are somewhat insulated from understanding the true costs of insurance premiums.

Bad for small businesses. It puts small businesses— which make up 99% of employers and 66% of new private-sector jobs— at a disadvantage. Since they don’t benefit from a larger pool of insured employees, it leads to higher administrative costs. The escalating cost of healthcare can be a significant burden for small employers, potentially impacting their competitiveness. (Don’t get me started on how hard it is to offer health insurance to employees of a startup with employees distributed across the country!)

Inefficient. These tax incentives can lead to overinsurance and the use of excessively generous plans by some individuals. This contributes to increased spending on low-value care and higher overall healthcare costs.

Regressive. But most concerningly, allowing healthcare insurance premiums to be excluded from income results in tax expenditures (subsidies) that are inequitably concentrated in higher-income individuals. In fact, research shows that lower-income families with employer coverage spend a greater share of their income on health costs than those with higher incomes. Families making under $52K annually pay 7.7% of their income on employer-based health insurance premiums, versus just 2.3% for high earners.

In addition to employer-sponsored insurance, many Americans receive coverage through government programs. These include Medicare, which provides health coverage for individuals aged 65 and older or with certain disabilities, and Medicaid, which provides health coverage for low-income individuals and families. The way I was taught to remember it was: we care for the elderly (via Medicare) and we aid the poor (via Medicaid).

Medicare and Medicaid

Established in 1965, Medicare and Medicaid are two critical payers. Together, they provide health insurance coverage for 37% of the US population (equally divided between the two).

Medicare is a federal program that provides health coverage for people aged 65+ or with certain disabilities. It is divided into parts A, B, C, and D, each of which covers different types of health services. It is administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and interestingly, administrative costs are only 2% (compared to about 17% for private insurers).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare, introduced significant reforms to the way Medicare payments are handled with the aim to improve healthcare quality and reduce costs. This included:

Value-based purchasing. This program adjusts payments to hospitals based on the quality of care they provide. Hospitals are assessed on a variety of measures, including patient satisfaction, the efficiency of care, and patient outcomes. Hospitals that perform better on these measures receive higher payments.

Readmission reduction program. To discourage unnecessary hospital readmissions, the ACA introduced financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected readmission rates for certain conditions. This incentivizes hospitals to improve discharge planning and post-discharge care to ensure patients don't need to return to the hospital.

Bundled payments. The ACA expanded the use of bundled payments, which provide a single payment for all services related to a specific treatment or condition, instead of paying for each individual service. This encourages care coordination and efficiency among providers.

The ACA also established the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), which encourages the formation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). ACOs are groups of doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers who come together voluntarily to provide coordinated, high-quality care to their Medicare patients. The goal is to ensure that patients get the right care at the right time, while avoiding unnecessary duplication of services and preventing medical errors. If an ACO meets quality performance standards and their spending is less than a defined benchmark, they are allowed to share in the savings they achieve for the Medicare program.

Medicaid is a joint federal and state program that provides health coverage to people with low income, including some low-income adults, children, pregnant women, elderly adults, and people with disabilities. Medicaid programs must follow federal guidelines, but they vary somewhat from state to state.

Most states require that Medicaid enrollees participate in Medicaid Managed Care. There are two types of managed care models (in addition to fee-for-service):

Managed Care Organization (MCO), where states contract with MCOs, which are private insurance companies. The state pays the MCO a set amount per enrollee (capitation), and the MCO is responsible for providing for their healthcare needs. The goal is to manage the care of Medicaid recipients more effectively and efficiently, potentially saving money and improving health outcomes.

Primary Care Case Management (PCCM), where states pay a monthly fee to primary care providers for case management (in addition to fee-for-service primary care).

Managed care is intended to help control costs while also coordinating care more effectively, particularly for patients with multiple healthcare needs. However, evidence on spending, utilization, and health outcomes is mixed. One of my MPH professors talked about the “Notch Effect”, when a Medicaid-eligible person has to make the trade-off between earning a higher income versus losing their Medicaid benefits. While it makes sense, I could not find any reliable and recent studies on the topic.

The uninsured

Despite these various forms of coverage, a portion of the American population remains uninsured. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 8.3% of the population are uninsured (as defined as not having health insurance at any point during the year). This nationwide figure, however, masks significant disparities among states. In 2021, the uninsured rate ranged from 2.5% in Massachusetts to 18.0% in Texas. These variations reveal the impact of different state policies, economic conditions, and demographics on healthcare coverage. Such a wide range points to the challenges in achieving universal coverage and also raises questions about equity and access, as those in states with higher uninsured rates face greater barriers to essential healthcare services.

Pharma: medicine, money, and middlemen

With 60% of US adults taking at least one prescription drug and 25% taking four or more prescription medications, the pharmaceutical industry is a key player in our healthcare system.

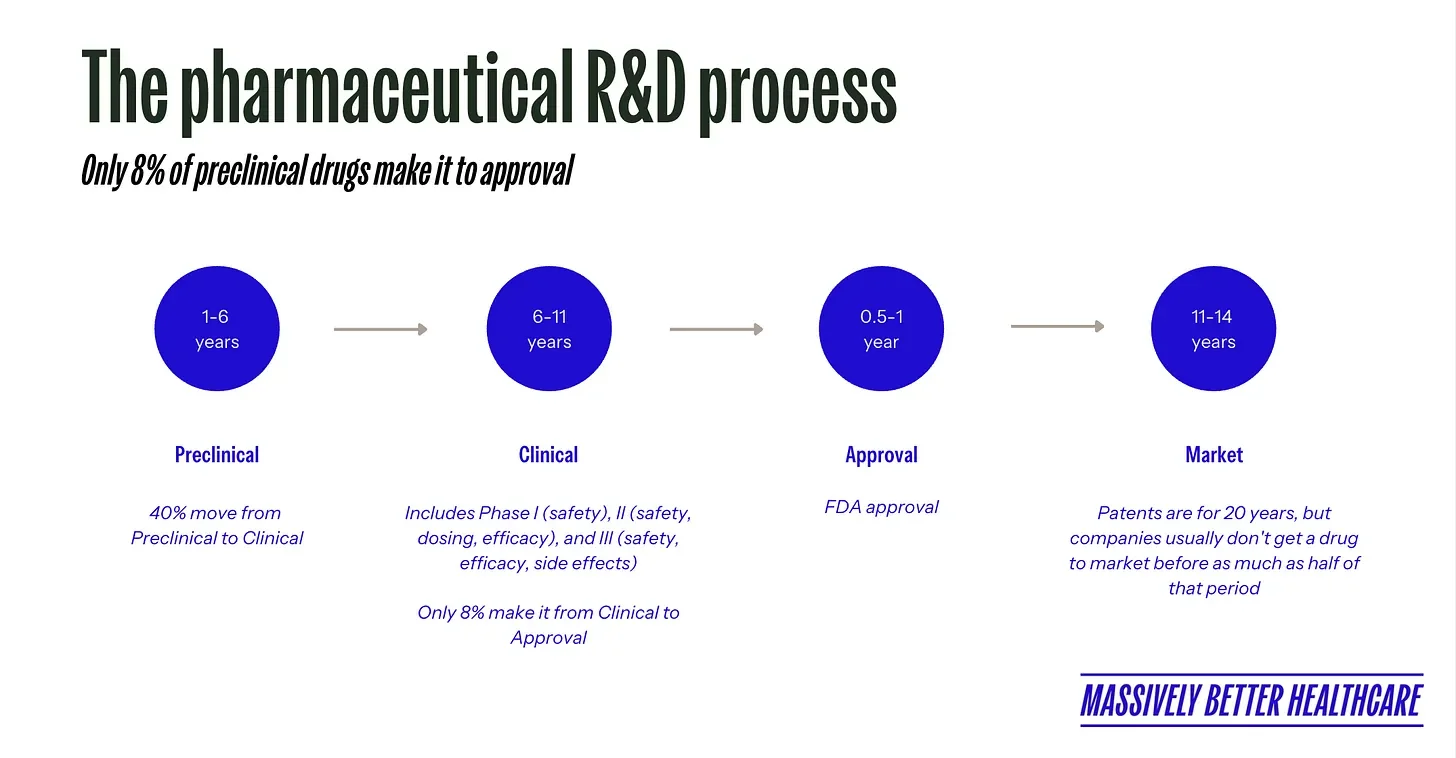

The US pharmaceutical industry leads the world in the development of new medicines, particularly in areas of unmet medical need. Fueled by extensive research and development (R&D) activities, pharmaceutical companies invest billions of dollars annually in the pursuit of new and improved treatments.

Why are drugs so expensive?

Prescription drug prices in the US are significantly higher than in other nations, with prices averaging 2.56x those seen in 32 peer nations. In 2019, we spent $1,126 per capita on prescription medications, compared to $552 per capita in comparable countries (this includes spending from insurers and out-of-pocket costs).

So why are drugs so expensive? If you ask pharmaceutical companies, they’ll tell you it’s because innovation is expensive. They’ll point to the fact that R&D costs as a percentage of sales is higher for pharma than other industries.

But if you talk to others, you may hear that it’s simply because pharma can raise prices on drugs, and no one (in the US) is stopping them. Pharma is the only major healthcare stakeholder that is able to exercise relatively unrestrained pricing power. They can set the prices paid by Medicare and Medicaid for new drugs. They also have the upper hand with private insurers, who are obligated to cover many new drugs.

But there's another way to look at this. In The Great American Drug Deal, biotech investor Peter Kolchinsky argues that expensive branded drugs should be viewed as a societal investment rather than an expense. Why? High branded-drug prices are necessary to grow our pool of inexpensive generic drugs. Since brand-name drugs eventually "go generic," they become dramatically cheaper while maintaining the same benefits. In contrast, he points out, the cost of healthcare services—like colonoscopies or knee replacements—only moves in one direction: up.

Are taxpayers subsidizing pharma’s R&D?

Every one of the 210 new drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 2010 to 2016 was associated with scientific research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This research — paid for by taxpayers — encompassed over 200,000 years of grant funding, amounting to more than $100B.

Public funding has been instrumental in basic research exploring the biological targets for drug action. And while it doesn’t fund the development of the drugs themselves, it certainly offsets some of the initial R&D costs that would otherwise be incurred by pharmaceuticals. So thank you, taxpayers, for laying the groundwork for many medical advances.

Given that large pharmaceutical companies have median net income margins of 13.8% (other large corporations in the S&P 500 are at 7.7%), some think taxpayers should benefit more from the research we fund. I’m inclined to agree.

Given that large pharmaceutical companies have median net income margins of 13.8% (other large corporations in the S&P 500 are at 7.7%), some think taxpayers should benefit more from the research we fund.

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)

PBMs emerged as a somewhat peculiar byproduct of the idiosyncrasies ingrained within our healthcare system. Operating entirely in the background, PBMs are (enormous) stand-alone businesses that manage prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurers, Medicare Part D drug plans, large employers, and other payers.

The primary purpose of PBMs is to negotiate with pharmaceutical manufacturers and pharmacies to secure lower drug costs for their clients. Their methods include implementing formularies (lists of preferred drugs), negotiating rebates from manufacturers, and establishing pharmacy networks.

Formularies are designed to encourage the use of lower-cost drugs, typically by placing them on lower 'tiers' with reduced copays. PBMs leverage the sheer volume of the potential patient base to negotiate rebates and discounts with pharmaceutical companies, who obviously want to have their drugs included in these formularies.

Some argue that while these rebates may lower costs for insurers and PBMs, they don't necessarily translate to lower out-of-pocket costs for consumers. In fact, the list price of drugs, which is the starting point for these negotiations, continues to rise, which especially affects the uninsured or those with high-deductible plans.

Wholesalers

Between your local pharmacy and drugmakers sits another middleman: pharmaceutical wholesalers. About 92 percent of all prescription drugs in the US flow through wholesalers, with just three companies—AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson Corporation—handling over 90% of this distribution. They help manage the drug supply chain, purchasing medications from manufacturers, storing them, and then distributing them to pharmacies, hospitals, and clinics across the country.

Wholesalers operate differently in the branded versus generic drug markets. For brand-name drugs, they're mostly "price-takers," typically making slim margins. But with generic drugs, wholesalers have more power to influence prices through their negotiations with manufacturers. If a generic manufacturer can't secure a contract with one of the big three wholesalers, they might effectively be locked out of the market entirely. Because generics make up 90% of retail prescriptions, wholesalers make more money from generics than brand-name drugs.

So how do wholesalers make money with such thin margins? One way is through forward buying—purchasing extra inventory when they anticipate a price increase, then selling at the higher price later. They also earn revenue through services they provide to pharmacies and manufacturers, from data analytics to repackaging drugs. While wholesalers capture only about $2 of every $100 spent on prescriptions, their position in the middle of the supply chain gives them influence over which drugs make it to pharmacy shelves and at what price.

Patients: the ultimate stakeholder (or should be)

At the end of the day, patients sit at the center of this entire system. Every move by providers, payers, and pharma eventually lands on us—for better or worse.

We’re the ones receiving care, taking medications, and trying to navigate coverage. But we’re not just passive recipients. Patients make daily decisions about their health, and to do that well, we need clear information, usable tools, and support. Right now, much of that is missing.

Too often, it feels like navigating healthcare blindfolded. Prices are hidden until the bill shows up, medical jargon is confusing, and coverage rules shift depending on the fine print. Many patients also say they feel rushed through doctor visits, like a cog on an assembly line. That lack of time and attention means we leave appointments without fully understanding what’s going on—or what to do next.

And when care involves multiple providers, coordination is weak. Patients end up with duplicate tests, conflicting advice, and sometimes dangerous medication errors.

Americans are not pleased with the state of our healthcare system

No surprise, Americans are unhappy. The US has the highest dissatisfaction with healthcare. A Gallup poll found only 48% of people rate the healthcare system as “excellent” or “good,” down from highs in the early 2010s. A record 21% now call it “poor.” One in five people believes the system is in a full-blown crisis. Cost is the biggest driver: 76% of Americans are dissatisfied with the increasing expense of care.

Patient engagement and empowerment

There’s been a lot of buzz around “patient engagement” and “empowerment.” The idea is to move away from the old paternalistic model where doctors tell patients what to do, toward a partnership model where patients have a say. Shared decision-making, for example, involves clinicians and patients jointly deciding on treatments.

But this isn’t just about individual behavior. It's also about changing the healthcare system to better support patients. This could involve everything from improving health literacy, to promoting patient rights, to creating patient-friendly healthcare environments.

Healthcare consumerism

Regina Herzlinger, often dubbed the "Godmother" of consumer-driven healthcare, was early in positing that making healthcare more consumer-centered would lead to increased efficiency, improved quality of care, and greater innovation in the sector.

Herzlinger has advocated for a system where consumers have the ability to choose their own healthcare providers and insurance plans. The rationale is that when consumers have the power to choose, it fosters competition, which can lead to improvements in quality, cost, and service. Consumers should have full access to information regarding costs and outcomes, which would empower them to make educated decisions about their healthcare.

And a key tenet of the consumer-driven approach is increased transparency in pricing and performance. Patients should have the ability to compare the prices of procedures, treatments, and medications between different providers or pharmacies, much like how they would compare prices for any other product or service. Likewise, transparency about provider performance would allow patients to compare the quality of care between different healthcare providers or institutions.

The idea is that a more consumer-driven healthcare system would spur innovation. When consumers are actively choosing and paying for their healthcare, providers are incentivized to innovate in order to attract and retain patients. This could lead to the development of new treatments, technologies, and care delivery models.

The future patients want (and need)

Right now, patients face a messy and frustrating system marked by high costs, rushed visits, and poor coordination. Dissatisfaction is rising, and trust is slipping.

The call for patient engagement, empowerment, and true consumerism reflects an urgent need for change. A better future would mean transparency that’s actually usable, care that’s coordinated across providers, and shared decision-making that respects patients as partners. It would also mean rewarding innovation that improves health, not just revenue.

For patients to move from the sidelines to the center, the system has to evolve. The goal isn’t just to make patients more “engaged”—it’s to create a healthcare model where being informed, empowered, and heard is the default.

Read more about the Healthcare Consumer Uprising.